On Route of Early Texas Streetcars

Marker Text:

In Bonham - as in most Texas towns that became busy trading, ranching, or agricultural centers in the late 1800s - streetcars or trolleys were used in local transit. Bonham's steam-powered streetcar line, built about 1890, extended 2.5 miles from Russell Heights to the Texas & Pacific Railroad Station. Cars ran every 30 minutes. Fare was 5 cents; or 10 cents round-trip. The route avoided the business district, as streetcars frightened horses and disrupted trading.

Other towns of sprawling growth had mule-drawn streetcars as early at 1875. These early cars were susceptible to track-jumping, collision, and other accidents, but were nevertheless welcomed for their services. Convenient streetcar rides attracted not only townspeople, but saddle-sore cowboys as well. By 1890, when Bonham acquired the steam-car line, mule-drawn cars were being replaced all over Texas.

Location: 10th & North Main Street, Bonham

Bonham's Era of the Streetcar

(undated newspaper clipping)

By Helen Evans Burow

Along about 1889, “Carter’s History of Fannin County” records the following announcement:

“Movements are on foot for a line of street railway, with the very probably addition of gas works. Many smaller towns, of much less wealth, have these conveniences, but Bonham in these matters will doubtless take her time, as she has heretofore in all other enterprises, but when they are completed the incorporators need have no fears of their failure.”

It is thought that the steam powered street car, which was called the “Dummy,” started in 1890 in Bonham. It ran from Russell Heights in the north part of Bonham, to the Texas and Pacific Railroad station, a distance of about 21/2 miles, every 30 minutes.

Four families in the Heights built the power plant near the old fairgrounds, the race track and Sinclair lake. Those families were the Russells (John and Jim), the Ernest Whites, the J. R. Raineys and the John Arledges.

Bob Bohannon ran the power plant and was the first motor-man for the car. Jack Russell, son of Dave Russell, was the secretary-treasurer of the corporation.

Several years later the street car became electrified.

At first, the car line went from the fairgrounds south on Cedar street to the corner of Tenth, where it turned east continuing to present-day Center street. It then ran due south to the old Steger Flour Mill on First street, where it turned west for one block, then south to the Texas and Pacific station.

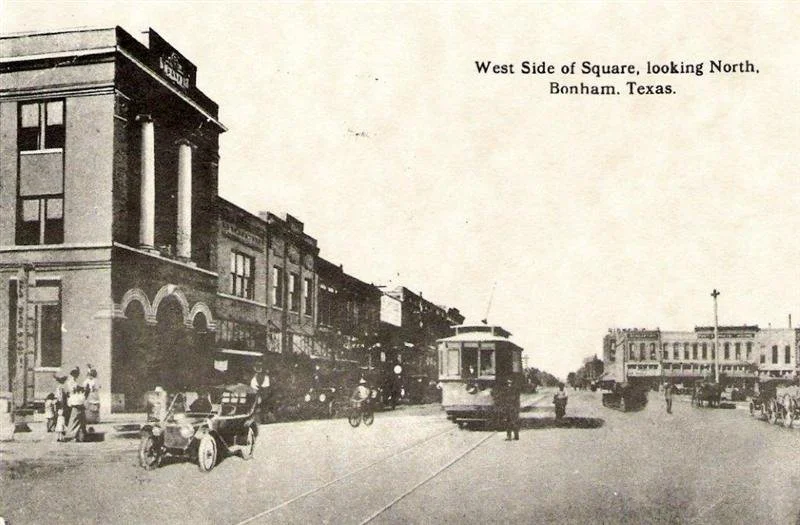

The reason the first street car did not go directly south on Main from 10th street was because the west side of the square was the place of the most flourishing business, and the street car scared the horses, thus interrupting business.

Center street was a much safer route until the electricity became in use and the car route went from 10th directly south on Main to the station, a much shorter and direct route.

The cost of riding the car one way was 5 cents, round trip 10 cents. The school children bought tickets for $1.25 a month, but businessmen had to pay $2.50. Of course, if a person got on the car with no money, he was allowed to ride free — for once, at least.

The street car served many functions. It was good transportation. It took people to the Log Rolling (or fair), to the baseball games (the Texas-Oklahoma league), to the races, to the natatorium at Sinclair lake. Of course, on busy occasions, flat oblong trailers were pulled back of the main enclosed street car. These trailers had seats on either side with an aisle down the middle. The passengers said it was a pretty rough ride, as there were only single wheels on the flat cars. It did not keep the many people from taking a nice ride, though, on a hot summer night.

Another service the street car rendered, especially to the housewives in Russell Heights, was grocery delivery. The lady would send a want list of groceries to the store. The motor-man delivered the list and on his return trip from the station, he would ring his bell in front of the grocery store, the goods I would be brought out and placed on the car. The housewife was notified by bell ringing and she would rush out and get her groceries. After the telephones were put in, it simplified the ordering of groceries.

As is to be expected a number of accidents were caused by the street car. Numerous horses ran away. At the corner of Sixth and Center, where the old Opera house stood, the car ran over and killed a poor deaf mute. It is also said that a Negro was run over and killed.

It is impossible to get the many names of those who served as motormen for it is said that every boy in Russell Heights ran the car at one time or another. The men remembered were Bob Bohannon, Pope Laurance, Ed Agnew, Claude Arledge, Homer Hayes, who now lives in Denison, Billy Smith, John White and Carl Abernathy.

The Katy railroad tracks ran just north of the present golf club, crossing Cedar street. One day the train hit the car, causing much confusion. Mrs. White was on the car. She was hurt, but not seriously.

The last accident remembered was about 1914. Stewart Arledge was motorman on the car. Mr. Arledge still recalls the shock when the chains on the car broke as he neared the T&P tracks, going down hill.

The car bounced over the railroad tracks and landed in Bedford’s hamburger joint on Powder creek. Rex Hendrix, still living in Bonham, was a passenger on the car and he and Stewart say now how funny it was, but how scared and shaken they were at the time of the accident.

Children studied their lessons coming to school on the car, but it was not all work, for it afforded many happy hours. Love affairs were even begun during street car rides. One even led to marriage. Miss Frances Brown of Roanoke, Va., came to Bonham to visit her aunt, Mrs. Jane Russell. The motor-man on the car during her stay was a handsome young man named Hill Edmonds. The courtship started and the two were married and moved to Virginia, where they raised their family. Mrs. Edmonds is still living in Virginia, but her husband passed away a few years ago.

There are many dates given as to when the street car ceased to run, but the best research we can make gives the date as Jan. 31 or Feb. 1, 1915.

Len Morgan of Bonham says that Mr. John Arledge, Sr., paid him $75 to take down the trolley. The tracks were taken up at different dates, but the last were removed during World War II when iron was needed so badly.